Understanding my father

Searching for my father

In the fall of 2022, shortly before my father passed away, I visited Korea. I wanted to see my parents in the beautiful autumn weather, and I hoped to express my gratitude and love once more before it was too late. I did not know at the time that his passing was so close. During that visit, I also arranged meetings with some of his former colleagues. I wanted to hear from them who my father was in their eyes.

Each colleague remembered him differently, as if each held a tile in a larger mosaic.

Sukon Kim, who had worked on his strategy team at Samsung Corning, called him detail oriented and strategic. He remembered a rare moment when my father apologized for not giving him more attention. Others found him intimidating, but Sukon said he always felt trusted. Listening, I could almost see my father’s careful smile, the one so often hidden at home.

His longtime assistant, Choong Pyo, described his discipline as almost mechanical — waking at five, heading to the gym, repeating the routine for four decades. Then he brightened, recalling how much my father loved noodles, especially 칼국수 (Kal-Gook-Soo), the hearty thick cut noodle soup in beef or clam broth with zucchini and clams.

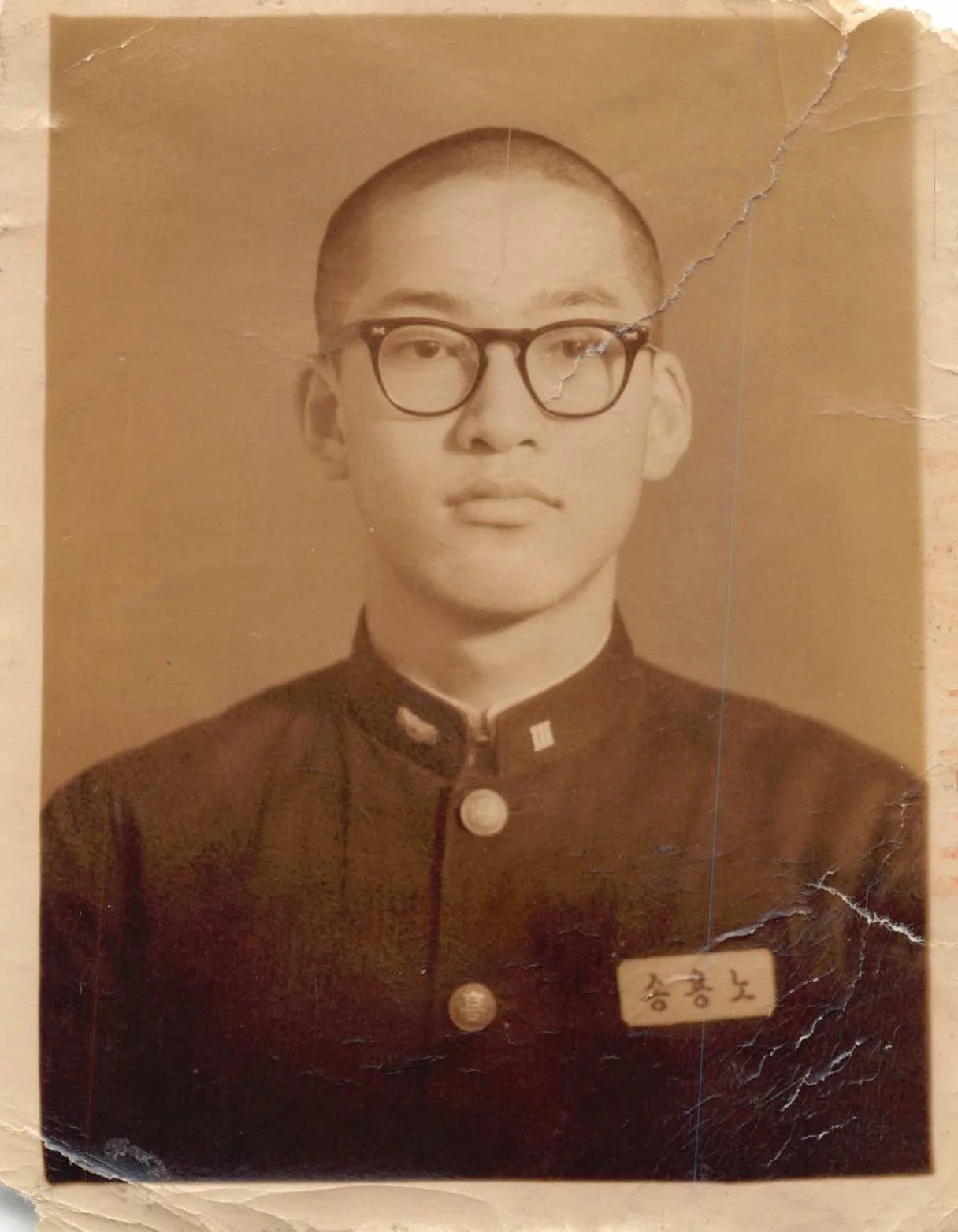

Another colleague, KyungHwa Chung, called him 모범생 (Mo-Beom-Saeng) — the model student. Professional, attentive, unlike many of his peers in senior leadership. In his forties and fifties he was strict, even feared, with sharp eyes and exacting standards. Later he mellowed, more willing to accept those who fell short.

I also met HyunJin Jeon, who had worked as his secretary for seven years while he was CEO of Samsung Corning. She described him as meticulous, demanding, and earnest. She remembered him as a man of few words and great consistency. He didn’t share much of his emotions. She said he brought her small gifts when he returned from business trips.

From the company’s perspective, he was a champion of change. He had turned divisions like cell phones, construction, SDI, and Samsung Corning into growth businesses. I still picture him traveling to China to negotiate with government officials, or sitting in an American courtroom during a legal dispute with a competitor. Grueling, yes, but those battles seemed to energize him.

When I told KyungHwa, his long-time colleague, that I had shifted my career to executive coaching, he smiled and said he could see the resemblance. He told me that, on many occasions, my father had been a great coach as well. I had always thought of him more as a mentor or teacher, never as a coach. Perhaps that was because our relationship was between father and son. But through KyungHwa’s words, I could imagine how my father might have been a brilliant coach, especially in his later part of the tenure, to his colleagues and team members. Hearing that made me feel validated in my own transition to coaching.

His life and career

He was born in 1945, the year World War II ended and Korea was freed from thirty five hard years of Japanese colonization. When the Korean War broke out, he was five years old. His family fled south as many did. His oldest brother and sister were left behind in the North. Or they voluntarily stayed behind, nobody really knows. From then on, no one ever knew if they are alive or living well in North Korea where there is no mail or human connections are possible. I first heard that story in my teenage years, told almost matter of factly.

I don’t think my grandparent’s family was very poor given that my grandfather was working for some kind of agricultural government office when my father was young. However, like most families in the late forties and fifties, they often lacked food. He and his brothers joked that they sometimes ate worms they found in the street for protein. At the dinner table his older brothers would tease him, flying their spoons like airplanes and landing on his bowl to steal his food. The story always made me laugh and wince at the same time.

During his military service in the sixties, his commander quietly sent him off base because the unit needed money for supplies. He was one of the few college students, so he earned cash by tutoring high school students. It was an early glimpse of the resourcefulness that would mark his career. He also shared he was beaten and hazed by his army seniors.

Korea in the 1950s and 60s was among the poorest countries in the world. When Park ChungHee, 3rd President of the Republic of Korea, took power in 1963, against the consensus view of Korea’s strength as being agriculture, decided to grow the economy through building manufacturing infrastructure in Korea. All large conglomerates were born or elevated in this period to serve the country’s growth. For my father’s generation, individual effort in service of organization’s growth, and therefore national progress felt unquestionable.

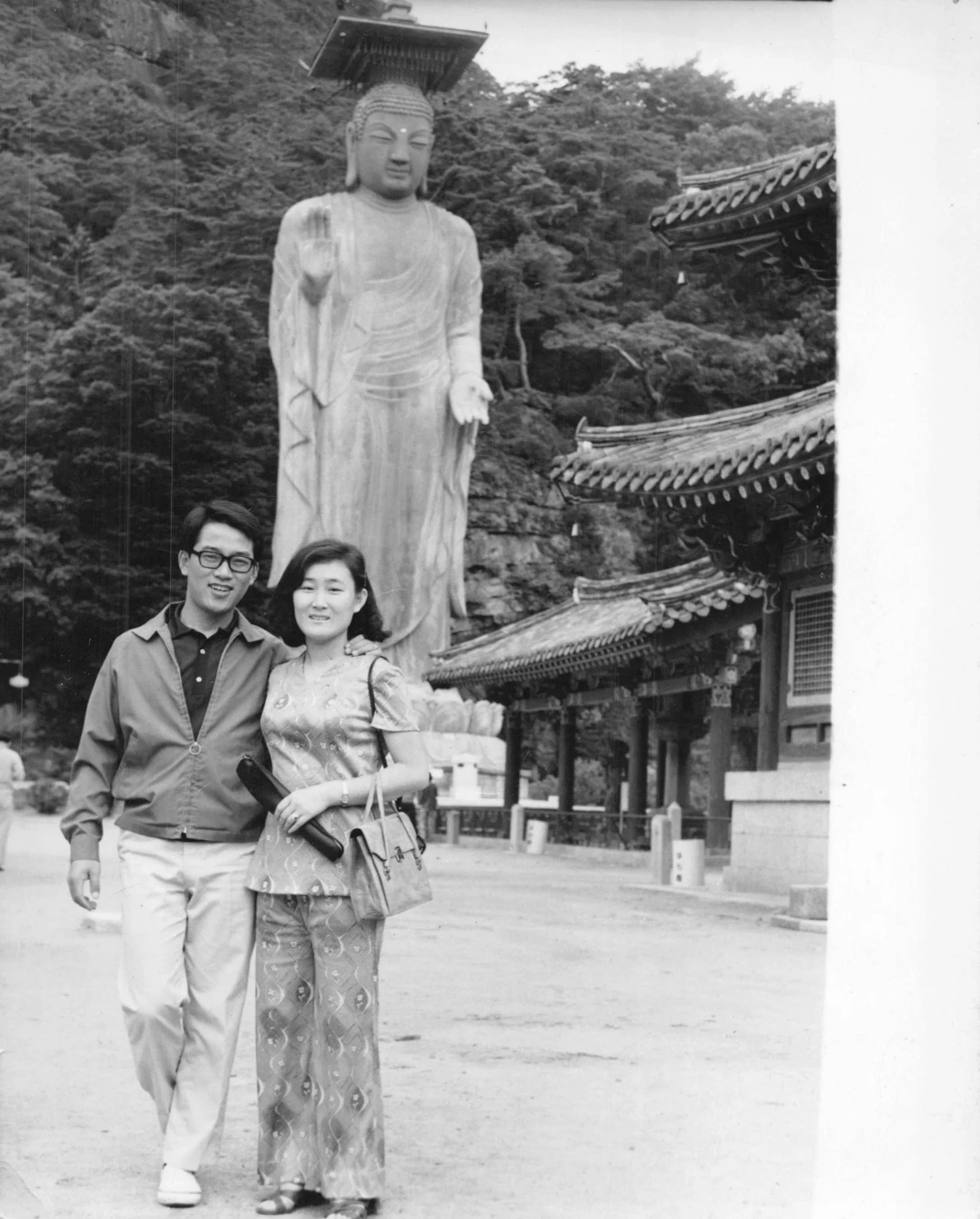

After graduating college and finishing military service, he joined 제일 모직 (Cheil Industries) in 1971, a Samsung company, and he stayed within the Samsung group until retiring in 2007. After some years working in accounting, he worked in human resources at the Chairman’s office building the entire Samsung group level training programs and overseeing executive reviews & promotions, then moved to Samsung Corporations where he led teams that exported Korean clothing to global markets. Years later, when I visited the United States, he told me how he used to visit and asked Sears, J C Penney, and other US department store chains to hire Samsung as an OEM manufacturer for their brands and open up shelf space in the US.

He rose quickly. At forty he became vice president of human resources at Samsung Electronics. Later he headed the entire cell phone division when wireless technology was going through a platform competition. I remember riding in his car and seeing five different brick sized cell phones scattered around the console. He would test calls on each one, comparing signal and voice quality of different wireless technology as if the car were a small lab. After that he served as CEO of Samsung SDI, where he helped steer the company away from liquid crystal display (LCD) panels toward lithium ion batteries. Today that battery business is known worldwide. Back then it looked like a risky turn that demanded conviction.

He spent his longest stretch at Samsung Corning, a 50-50 joint venture with Corning Incorporated. He saw that cathode ray tube (CRT) glass would not last as flat panels took over. He tried to pivot the company into new businesses, but Corning did not support the idea. For them the venture still was a cash cow. They would rather squeeze more cash and let it die. For him it was a community of people whose livelihoods were at stake. I watched it in my late twenties. I understood Corning’s economic logic. But I hoped my father’s effort to create a new lifeline would succeed.

He once shared an episode with an American counterpart. For a top executive’s visit to Korea, he and his team carefully searched for a restaurant that would showcase Korean cuisine and hospitality. When the guest arrived, the first thing he asked was whether he could have steak for a meal. My father must have been disappointed — he repeated this story many times. I have been using this episode, in my cross cultural facilitations, as how we can be better in trust building through relationships. Still, he was proud to represent Samsung and the joint venture during that period, hosting and attending C-level summits and leading critical and contentious negotiations.

A colleague of his once told me he felt sorry that my father was often thrown into the hardest challenges at Samsung, precisely because he was known for figuring things out during crisis and driving change. That was true. He made a real impact in each of those situations, and I think he also found genuine excitement and enjoyment in leading the organizations in transitions. Watching him in those moments in distance, I felt proud of him.

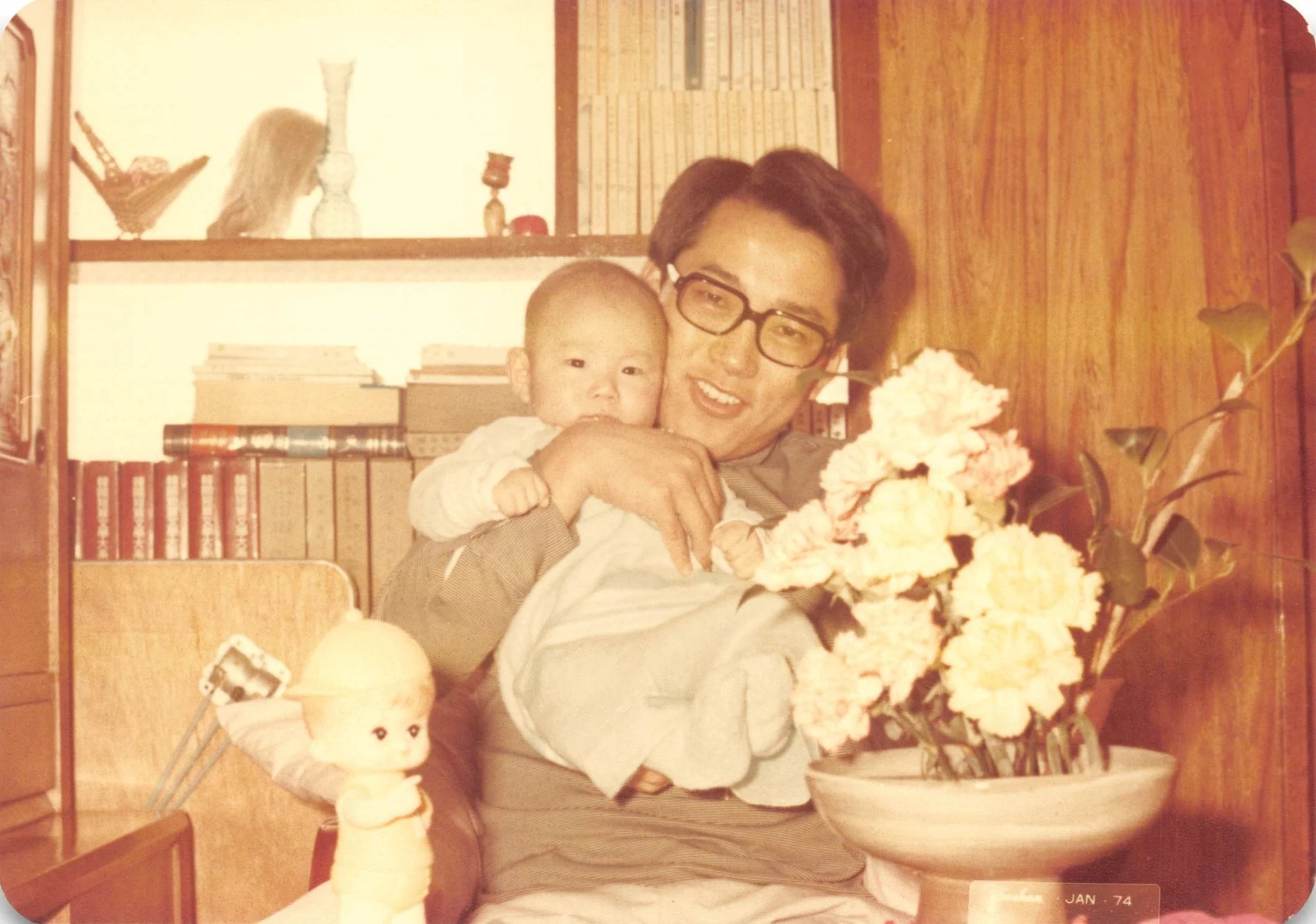

Memory of him when I was young

When I was in grade schools, my father was very busy. Most evenings he came home late, and weekends were often filled with golf or work. When I was young, I wanted to spend more time with him. I don’t know why (I wasn’t really a baseball kid) but I had a fantasy of playing catchballs with my father in a narrow space between apartment complexes. We did it only once or twice, I believe. When he traveled for business, he brought back gifts — toy cars, other fancy toys, and CDs I had asked for. I always looked forward to those.

I do not recall him sharing or repeating any specific life lessons with us, like being kind, contributing to the world, or helping others — the kinds of things people often mention when remembering their parents’ teachings. His specific words I remembered are more connected to how to work successfully in the corporate world. “주도면밀(周到綿密) 해야한다” (be thorough and meticulous at work), “be aggressive,” “have a can-do attitude,” and “family is important” Beyond those, most of his lessons came not in words but in actions.

If I had to sum him up in three words, I would say competitor, strategist, and romanticist. His work and career defined him more than anything.

He worked tirelessly. Work came before family. At that time in Korea, when the nation was rebuilding, this was seen as necessary. His company, Samsung, contributed significantly to that growth, and he gave it his all. I respect this. At the same time, I see it differently for myself: his example led me to swing more toward family and meaning in life I believe.

It’s not that he didn’t show kindness though. His kindness was supporting his extended family. He felt deep responsibility in helping his siblings, mom’s siblings, nieces and nephews. Like many other Koreans, he had a strong sense of protecting his family. Many of his nephews and nieces—perhaps almost all of this large family - got significant help in getting their jobs, like I was able to get into the finance team at Samsung. He provided financial support for his siblings, and for my mother’s side of the family, for many years. He wanted my brother and I to be close with our cousins. At family gatherings, he often gave tough-love advice, which was not always well received, but came from his sense of responsibility.

When I applied for college, I did not think much about my choice of major. In the early 90s in Korea, all students had to declare a major when applying for colleges. I vaguely assumed I would work for a for profit corporation like my father, so “business administration” seemed natural. I ended up choosing economics because it was slightly easier to get into with my exam scores and adjacent to business major at Yonsei University. I knew nothing about economics.

In the early 1990s, psychotherapy was not well known in Korea. I saw a notice on the student center bulletin board and decided to try it. I went there and talked about my relationship with my father. I do not remember the details, but I know I spoke about how to manage his expectations of me as the main challenge. The interesting thing is that I do not recall him saying very specific things about how I should live or what job I should take. And yet, I felt pressure.

In my last two years of college, I studied for the CPA exam. It was a once a year national government driven exam and required an enormous amount of study time to get in. Again, I do not remember thinking about why. It just seemed logical to pursue some qualification. Honestly, I knew I was not working hard enough and would not succeed. And yet, I spent two years of most of my free time on it. I wanted to show others that I was doing something for my career. Why didn’t I explore other career paths — talking to people in different fields, joining career clubs, trying different things?

The same pattern followed me into my first job search. I applied for Samsung Electronics after two failures at the CPA exam. Samsung Electronics was the most prestigious company in Korea, and my father worked within the Samsung group. I did not even consider applying anywhere else. I was placed in the headquarters corporate finance team, the treasury department, where we manage cashflow internally, execute M&As and strategic investments, and work closely with banks and other financial institutions. It was not too far from the economics major I chose. Many new hires coveted a role in the headquarters finance team, and I was fortunate that my father’s influence helped me secure it. The CFO, head of all corporate finance of the company, had once been my father’s direct report.

Father - son relationship as adults

In my late 20s and early 30s at Samsung Electronics, I wanted to talk openly with my father about the company’s culture, and Korean work culture in general. I thought that he must have felt the same frustration I had. Also, I wanted his approach to them. I remember asking, “Why do managers use corporate credit cards to buy lunch for their colleagues almost every day?” I also wondered about unreasonable requests from superiors and the automatic obedience to them. Even though I didn’t grow up feeling restricted about sharing my opinion, I immediately understood what it meant. Seeing everyone around me behave with such deference to their seniors on small things and big things, I remember feeling it was not possible to share my opinion that is different even though my opinion could be helpful. Did he feel the same way? Would he remember the time he was young, not the boss? Even as a CEO, he had a boss, the owner family of Samsung. That must have given him similar challenges.

Another example: At Samsung, annual performance reviews were less about honest feedback and more about politics — a way to promote someone strategically.

I tried to talk to my father about these things, but he was not open. I think he listened. I don’t think there was any meaningful back and forth. He probably knew many of the flaws himself, but after more than thirty years in the system, I am guessing, it was difficult for him to criticize. I could not understand then why a father would not want to be open with his son about these life inconsistencies even if that could be being a little bit more vulnerable than usual. I did not realize how deeply he had assimilated into that culture and how powerful losing face could mean by being vulnerable.

In college and early in my career, I used to say that my goal was to “be happy.” I wanted to work fewer hours than he did. Maybe what I really wanted was to ask him if he was happy. I didn’t know what “happiness” really meant, but I used the word as a contrast to his life, maybe sarcastically. Years later, when I left Samsung, he looked at me and asked, “Are you trying to be happy?” Dad, I’m sorry for the sarcasm then and for not understanding you better.

Right before leaving one of the family dinners with my parents, my wife, and me as a newly married couple, my father said, “Joonki, Juhyun, let’s do our best to communicate well. Let’s share only good things, and let’s not share unpleasant things.” He was offering what sounded like life wisdom, almost setting a norm for this new relationship between young couples and them. It was a beautiful family moment, except the message felt strange to me even then. In warm and loving moments, it stood out to me. Years passing by, I interpret it as his deep wish for positive relationships with his adult children, shaped at the same time by the cultural and social norms of “saving face” at all costs. Probably to the contrary to his wishes, this little exchange added to the sentiment that my wife and I wouldn’t or shouldn’t share negative things, disagreements with them.

Recently, one of my close friends shared an exchange he had with his cousins after his uncle passed away. At first, he debated whether to attend the funeral since it was a bit far. He decided to send a floral arrangement as a tribute, as many people do for family funerals in Korea, so that the place would be brightened during the three days of receiving visitors. Later, he chose to visit in person.

During his visit, he was struck by how deeply his cousins — the son and daughter of his late uncle — expressed gratitude for the flowers he had sent earlier. Reflecting on this, he said, “We are still living with the concepts of 예 (禮, ye) and 허례허식 (虛禮虛飾, heorye-heosik) even in the year 2025.” 예 (禮, ye) is the Confucian idea of showing respect and harmony through proper rituals and courteous behavior. 허례허식 (虛禮虛飾, heorye-heosik) is when those rituals lose their spirit and become empty formalities or showy displays. He continued, “All of this feels like waste and showing off. And yet, many people still view those who do not follow these saving-face rituals as lacking the very basics of being human.”

It is ironic though now that I think deeper. My father was a change manager at work for a long time. He led big six sigma initiatives and culture building - which is basically appearing mistakes and failures fast to solve those issues. So he’s no stranger to the importance of sharing failures and mistakes at work for a better solution. And yet, he couldn’t see the merit of embracing that in our relationships. To my father, sharing only positive things was very important even in the relationship with his son and daughter-in-law.

I developed a very special relationship with a German couple, Horst and Regine, who were about the same age as my parents. I first met them in Munich when my friend JungHoon and I traveled to Europe during our freshman year of college. They were friends of my friend’s parents, and we had their contact information in case of emergencies. When we visited Munich, Horst and Regine welcomed us warmly and opened their home to two stranger kids for more than a week. From then on, I returned to Munich more than a dozen times, and even chose to work there during my MBA summer so I could spend more time with them.

Over the years, we shared many dinners and conversations that touched on nearly everything: history, art, travel, current events, cultural differences, and family life. History and art came up often, sparked by their visits to exhibitions or concerts, and those discussions lit my curiosity. I called Horst my “Working Dictionary” because he always had knowledge to share. They also spoke openly about their personal lives. I remember asking why they didn’t have children, how they first met, and even about past relationships. Regine told me about her difficult relationship with Horst’s mother and her earlier experiences in which intimacy lacked depth or connection. These conversations were startling in their honesty. I could ask anything. They made me feel safe and trusted. Despite different languages, cultures, and generations, I felt deeply connected with them. Being with Horst and Regine filled me with tearful joy. I felt loved, supported, and intellectually free in a way I had never experienced before.

This stood in contrast to the relationships I had with my parents or other adults in my life until then. I was curious about life — how it works and why we are here — but I never felt I could have truly open conversations about such questions with them.

My relationship with Horst and Regine opened a new possibility of a new way of living and horizontal and mutually supporting relationships with other adults. They worked hard, but only 9-5, to make money and found meaning through after work social life, arts, and traveling. Meeting them pushed me hard to pursue my MBA studies in the United States. Studying a graduate degree in the US seemed like a great combination of making my parents proud and experiencing something new. After those two years in the US, returning to work at Samsung felt one directional, one dimensional, and formulaic. I was against hierarchical work culture before my MBA. But, the experience in the US sharpened my awareness of how limiting hierarchical work cultures could be.

After retirement and diagnosis of Parkinson’s

In 2007, when he was 62, my father retired from Samsung. Or rather, the company moved him from President and CEO of Samsung Corning into an adviser role, a path often used for executives at that level. People said this was how Samsung prevented senior leaders from taking their knowledge and networks to another company. For three years he received a substantial salary but had very little to do.

I do not know exactly when or how he first received the news, but in my memory he was surprised and disturbed as if he was blindsided. It would not have shocked me if he first learned about his transition by reading it in a newspaper article, the same way some of his earlier promotions had been announced. For a man who had lived his life in ten-minute blocks, suddenly having nothing to do was a hard transition. To say he was unprepared for retirement would be an understatement. How ironic is it that he was unprepared for his future when his whole life was planning for companies’ future - short-term and long-term future?

Coincidentally, that same year I also left Samsung after eight years with the company. I flew to Brisbane, Australia, where my parents were on a golf trip, to share the news with them. I remember feeling more worried about how he would react than about the decision itself. In truth, I was convinced and passionate about my move. Deep down, I secretly hoped he would encourage me.

When I told him I had decided to leave Samsung to try something different, he responded, “If you’re going to just share your decision and not listen to my opinion, why even bother telling me?” I never told him directly that I value his advice, but that I also need to make my own choices. Looking back, that might have been the right moment to say it. His anger and frustration didn’t last long, though. Underneath, he was simply worried about me and my future.

Within two or three months of doing essentially nothing, he was already bored. I asked if he would consider working for another company or taking a teaching role at a university. But he rejected the idea. He told me he could not work for another company because it would look as if they were taking advantage of his former position as CEO of a Samsung affiliate. I could understand his loyalty, his sense of pride, and his fear of losing face by using his connections, not his knowledge, wisdom, and leadership. At the same time, I could not help but notice that many of his former colleagues found ways to continue working in later life — in academia, in advisory boards, or in more relaxed roles where they still carried influence.

Around that time, my brother told me he had decided to divorce. He asked how he should break the news to our parents. I could see the pain he was in and how desperate he felt. When he finally told them, my parents were shocked and upset. I said I would support his decision, and my father exploded, saying, “You are not my son.” I think he was more upset with me than with my brother. What disappointed me the most was that both my parents seemed more concerned with social impact and how they would explain the divorce to extended family and friends than with my brother’s pain. From their perspective, this was one of the most devastating losses of face a family could endure in Korean society, and for them it was unbearable. But the truth of the matter was the divorce rate in Korea was one of the highest in the world. People were just not sharing this news with anyone. My mother still says that those were the hardest years of her life. In time, they came to understand my brother’s situation and supported him. But they did not share the news openly for a long time, not even with close friends.

Only two years after his retirement, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. My parents had dreamed of traveling in retirement, but those dreams ended quickly. Looking back, we think the disease may already have been affecting him in his final years at Samsung.

He refused to let others know. Illness, to him, signaled weakness. Instead, he carried the same mindset that had guided his career: “I can do it.” He told us, “The doctor said regular, rigorous exercise can slow the progress. I will work so hard that I can live as long as if I didn’t have the disease.” Every morning, he repeated his affirmation: 나는 할 수 있어 — I can do it.

Since our family moved to Boston in 2008, our connections with my parents became more sparse, technically harder, and often misunderstood. On weekly video calls, my father’s voice became softer, we ran out of topics soon, and kids got bored quickly. We were not truly connected. I visited Korea three or four times a year for work and saw my parents during those trips. On those visits, my father often shared his envy of friends whose children lived nearby and visited regularly.

In 2013, I was offered a job that would take our family back to Korea for three to four years, managing the Korean branch of a U.S. company. It was a huge career opportunity—a chance to act as a kind of mini-CEO for a business unit. But for my wife, it felt like a crisis.

For more than ten years of marriage she had struggled with my parents, though distance in the United States had kept the pressure bearable. Preparing to live in Korea again meant facing them regularly, and the thought became unbearable. One day, she told me she would no longer meet or talk with my parents.

From her perspective, she had been constantly asked, pressured, and talked down to by my parents: “When can we have a grandchild?” “Why don’t you teach your kids more Korean?” “The trees around your house look dangerous—why don’t you cut them?” “Why don’t you prepare really good gifts for so-and-so’s birthday?” She felt suffocated by the impossibility of saying anything other than yes. I had not realized how helpless and hurt she felt, because in front of my parents she was always cheerful and agreeable.

I knew she carried some resentment, but I had no idea how heavy it was. At first I couldn’t understand. “Don’t all Korean parents ask those kinds of things?” I thought. “Isn’t it just part of the game, where you nod, then quietly do what you think is best?” For me, it was a game. For her, it was real pain. She stopped answering their video calls and told me she would neither explain herself nor see them once we moved.

My parents, meanwhile, were overjoyed at my family’s return. They have been jealous about friends’ trips with their children’s family. They secretly hoped I might stay in Korea permanently after this assignment. When I shared my wife’s decision, they were shocked and puzzled. To them, she had always been lovely and caring. It felt like another humiliating moment: I worked so hard my whole life for my family to be healthy, successful, and loving each other - why do I deserve this?

When my company held the grand opening of our new office in Seoul, my parents came to celebrate with us. My CEO flew in from the United States, along with other distinguished guests. About two years later, I received an award from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of the Korean government for contributing to the stability of the Korean electric grid, and they attended that ceremony as well.

For my career, those were the most dynamic, exhilarating, and challenging years. My unit accomplished more than anyone had imagined. At the same time, I was let go from the country manager position after receiving negative feedback from employees. That experience pushed me to question who I was, what I wanted, and how I could grow into the best version of myself.

I longed to share this journey of searching for myself with my father and to talk it through. Yet, I chose instead to bring my parents into the spotlight moments — just as my father once asked of me, “let’s share only the positive things.” Still, I am grateful that I could make them proud in those moments.

Collapse

By then, his health was worsening. He was still mobile, but much slower, and needed my mother’s constant assistance. His medication caused severe hallucinations. I saw him in horror seeing some kind of creature haunting him. He also accused mom of wrongdoing for no reason. He refused to let my mother or me share anything about his condition with others. He wanted her by his side at all times, and she gave up almost all of her social life to care for him. She was losing her mind. My mother became exhausted and depressed from the relentless care. For years she managed to help him alone in their apartment, cut off from others. Eventually she called me in tears, saying she could not continue. Soon after, she began showing signs of depression and early dementia.

On one visit, my brother and I sat down with them and suggested bringing in professional help so our mother could have some time for herself. My father looked at us with a mix of terror and fury, as if we had come to escort him to the next life. In the summer of 2018, while walking outside on a hot day, he collapsed. Soon, they had moved into a retirement complex, with my father in the nursing unit and my mother living in a neighboring building. After that, he became largely immobile and uncommunicative. The moments of real connection grew fewer.

Since his collapse, I’ve had only a handful of moments of genuine eye contact with my father. His words are no longer recognizable. During COVID, no guests were allowed to get in the nursing home. So, instead, we saw him through a plastic wall and intercom. He rarely made eye contact with me or smiled at me. His reaction and expression had probably more to do with his illness. But, I felt guilty and ashamed seeing his remorseful expression. It was deeply saddening to realize father and son are not able to connect in their later days. Also, I could also sense that both my parents were unable to move past the stage of denial about his Parkinson’s. Each time I visited, I said I love him as if that might be what he wanted to hear.

I often wonder how he would review his own life. Would he see it as fulfilling? Would he look back with appreciation on the hard work, challenges, joys, and achievements of his long career — a career spent working with and influencing so many people? How would he think about his relationship with his wife and with us, his sons? Would he also feel pride in those parts of his life?

I believe he took his mission and responsibilities very seriously, and that he also found deep joy in tackling challenges and making a lasting impact through his work. His sense of fulfillment went beyond reaching the top of an organization. Yet, perhaps because of those very achievements, his last fifteen years may not have felt as meaningful or satisfying. I wrestle with how to make sense of that contrast.

Maybe my recent memories of him carry more weight, which makes the later years color my picture of his life in darker tones. I worry that he himself may not have seen his life as fulfilling at the end. But does it matter? It is true that Samsung and the Korean economy he served occupied more of his time and energy than his family. That’s meaningful whether or not he chose to do so.

The same week I saw my fathers’ former colleagues for conversation, my brother and I faced the decision of whether to approve a medical procedure that could prolong his ability to eat. The doctor assured us the risk was minimal. My father still seemed strong, at least physically, so we agreed. On the way to the hospital, I sat beside him, holding his hand, unsure if he understood what was happening.

A week later, back in Boston, I got a phone call. He passed away. The procedure had gone well, but his body did not adjust to the eating through tubes, the doctor said.

Impact

My father has been a source of strength when times were hard, a source of anger and resentment, a standard for excellence, and a constant reservoir for reflection, writing, and self-awareness. Writing this book has reminded me of him again and again. I feel grateful about the opportunity to think beyond my surface level feeling toward him.

Many would remember him as a man of hard work and foresight in business, consistent and steady as a leader. But beneath that, I sense he was also soft, introverted, and warm, covering insecurities and qualities that did not fit the mold of a leader in his era. In pushing himself to become the person he needed to be to succeed, he sometimes lost touch with himself. For Korean society and the economy, that may have been a blessing. As his son, I wish he could have been more attuned to who he was. Yet I also wonder — if he had been more aligned with himself, would my complaint about him simply have been different? I’d still like to ask this hypothetical question. If he found paths that are more aligned with who he really was, would he have been more fulfilled in his life? I hope so.

When I left Samsung to move to the U.S. and carve my own path, that created tension between us. He had strong expectations about how I should live and what job I should take. It was a heavy burden, but also, paradoxically, the pressure pushed me to the edge and helped me take a risk and find my own way. Those years overlapped with his difficult retirement and his Parkinson’s diagnosis. He wanted me to return to Korea, to be near him. I visited him on business trips, but instead of sharing warm company, we often found ourselves in moments of discontent. I wish I had done better at showing love and appreciation in those times.

Still, I respect him deeply. I’m grateful for the stability he provided at home, the financial security, and the education he made possible. Only because he gave me so much am I in a position to complain about the warmth and compassion I felt lacking. But perhaps that is selfish of me. It reminds me of the poem by Dick Lourie, “How can we forgive our fathers?”

And shall we forgive them for their excesses of warmth or coldness?

Shall we forgive them for pushing or leaning,

for shutting doors?

For speaking through walls,

or never speaking,

or never being silent?

(From How can we forgive our fathers by Dick Lourie)

I wish I had done a better job of sharing more, softening my emotions, enduring his sarcasm, and finding ways to love each other better.

I also feel guilty about portraying him in the way that reveals his other sides people might have not known. I am worried about being judged. Am I worried about losing face? At the same time, I feel complete, more connected and fulfilled by spending much time searching for memories of him and trying to share every relevant thought and feeling I have. Without these stories, it would be hard to talk honestly about my self-authoring journey. I hope that by sharing them, I can also make him proud.