Title: The mother-in-law test

Subtitle: Self-authoring as a Korean American

Thank you for taking the time to read my book overview and excerpt and for sharing your thoughts!

As an executive coach, I've identified three core challenges that I have been working on over the past several years: 1) effectively challenging clients who are older than me, rather than defaulting to the view that they have everything figured out; 2) being judgmental of those who are reluctant to take risks for change; and 3) fighting the urge to tell clients what to do instead of coaching them to find their own solutions.

The first two challenges are deeply connected to the culture I grew up in. The underlying cultural values that contribute to them—filial piety, deference to authority, and group-based thinking—supported me in many ways during my early career. At the same time, however, they also hindered me from becoming a better version of myself.

Realizing that my cultural values were deeply connected not only to these professional challenges but to others in my life was a long and revealing process. For me, the real work began after I was let go from a job I had dreamed of—one that had made my parents proud. Through coaching numerous young leaders and seasoned executives, I've seen that many grapple with a similar inner conflict: a tension between how they believe they *should* live and lead versus how they truly *want* to. I am particularly drawn to supporting Asian and Asian American leaders who are driven and often quiet, and who tend to view vulnerability as a potential loss of face.

The first section of the book explores the concept of "self-authoring"—the journey from living within a framework of inherited expectations to consciously writing one’s own story. Drawing on Robert Kegan’s Adult Development Theory, I explain why this transition is essential not only for effective leadership but for a fulfilling life.

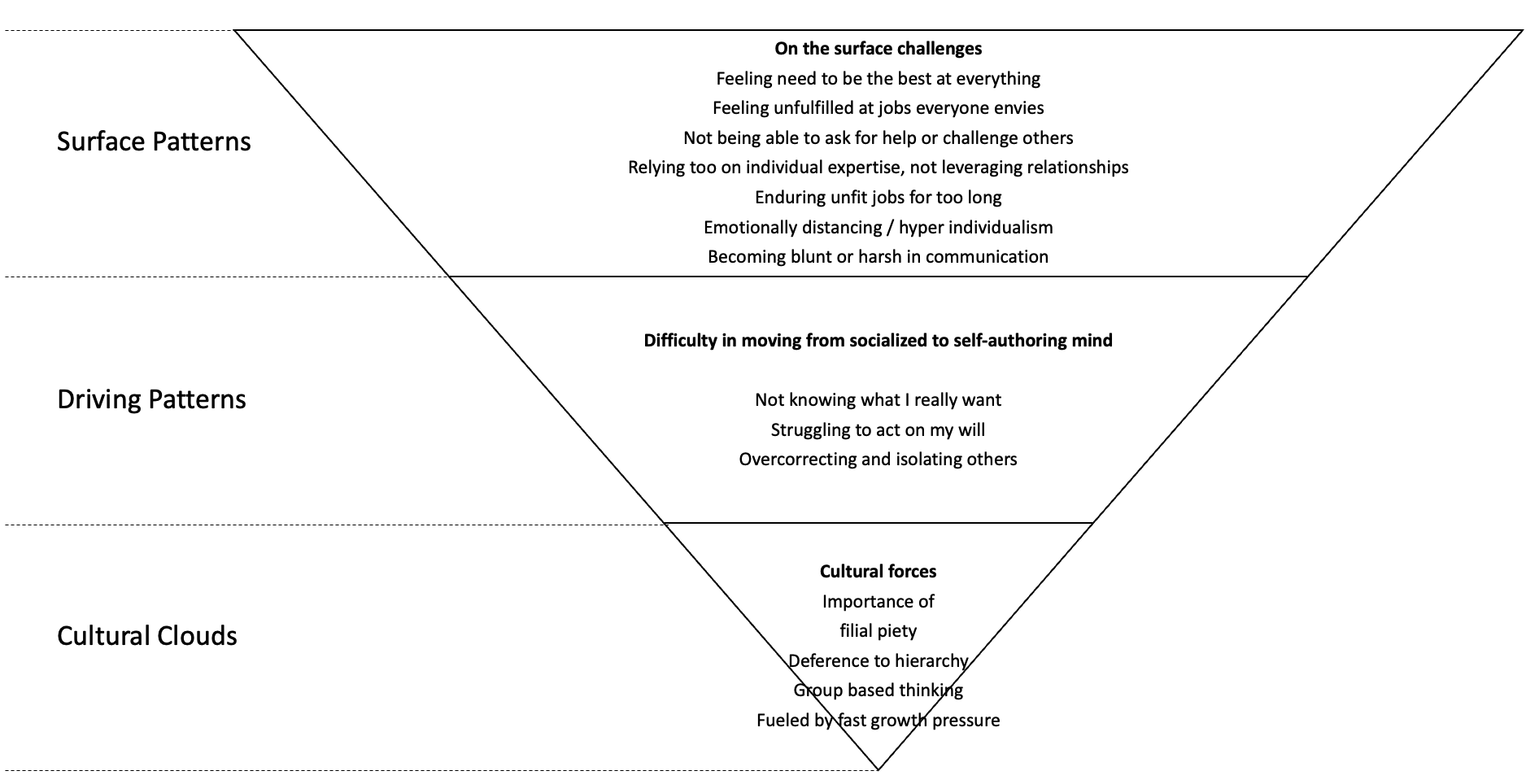

The second section examines why this journey of self-authoring is particularly complex for many Asian Americans. Cultural forces such as filial piety, group-based thinking, and deference to hierarchy can nurture gratitude and resilience, but they can also discourage questioning authority, setting personal boundaries, and finding the courage to do things differently. A striking example of this is the "mother-in-law test" in Korea, where young men evaluate life choices by asking how they would be judged by a future mother-in-law—a shorthand for how deeply family expectations and social approval can shape personal decisions. In my coaching practice, I see these hidden influences manifest in familiar patterns: a relentless drive to excel, the narrow pursuit of "safe" career paths, a reluctance to speak up in the face of authority, or a surprising harshness that erupts under stress.

The final section offers a path forward. Self-authoring is not about rejecting one's family or culture. Rather, it is about developing the clarity to see how those forces have shaped us, and then consciously choosing which values to carry forward and which to release. This work can feel risky, even disloyal, but it is ultimately what frees us to align our unique talents, personal values, and true purpose.

I write for Asian American leaders—and for anyone who feels caught between external expectations and an inner voice longing to be heard. This book is both a mirror and a map for that journey.

Except 1 - The mother in law test

Except 2 - Failure: The fast road to self-authorship

Framework - Cultural patterns and clouds of Asian Americans

Target Audience

Primary: Asian American professionals navigating careers in business, tech, consulting, and academia who wrestle with how they can be more effective in their leadership.

Secondary: Broader young adult to mid-career leadership audiences (20s-40s) interested in personal development, authenticity, and cross-cultural dynamics.

Tertiary: Parents, educators, and coaches who want to better understand the experience of Asian American young adults.

Outline

Introduction

My story of growing up working hard for achievement and being clouded at the same time under filial and group-based expectations; reflection of my journey in early 50s.

How I decided to write this book; what audience will take by the end of the book; introductions of book structure

The work of self-authoring as Asian Americans

Definition of self-authoring and how I chose the concept as the core for sustainable and effective leadership

Why self-authoring is particularly difficult and important for our life and leadership journey

The cultural clouds

How stories and examples such as “mother-in-law test” of three key cultural clouds - Importance of filial piety, group-based thinking, and deference to hierarchical norms - have impacted our success, mindset, and confusion.

Seven leadership patterns

Seven leadership patterns I observe through coaching with Asian Americans and how they are connected to cultural clouds

Courage for clarity

Why it is hard to see myself and the situation clearly, how taking courage to see myself is important for moving forward

How to: make sense failures, turn myself from actor to author; coaching story examples

Experimentation for change

Experiment as a building block for change

How to: design, execute, reflect from experiments; use coaching for effective experiment; coaching story examples

Overcorrection and resilience

Overcorrection as common roadblock for change

How to: recognize and move beyond blocks on the way; coaching story examples

Deeper contracts and paradoxes for self-authoring

Meaning of family and relationship as an Asian American

Making sense of loyalty and conformity

Managing self hypocrisy

Practical toolkit: Combining all tips across different chapters in one place with practical to-dos

Author

Joonki Song: Founder of Shimoo Partners, an executive coaching and consulting firm working with numerous Asian American leaders including MIT Sloan business school MBA, Sloan Fellows, EMBA program students. Frequent facilitator of leadership offsites, cross-cultural workshops, and executive coaching programs.

20+ years of professional experience across Korea, China, Japan, Taiwan, Germany and the United States, including corporate leadership roles.

Writing presence: personal website with published articles (on Asian American leadership, culture, and coaching).